Despite increasing geopolitical uncertainty and thre pressing need for economic development, it is climate change that most concerns Pacific leaders.

As 18 Pacific nations—including Australia and New Zealand—gather in Tonga’s capital Nuku’alofa this week, numerous concerns will occupy their talks, but none more pressing than the effect of climate change on some of the world’s smallest nations, according to a report from the Sydney-based Lowy Institute.

“Climate resilience will increasingly be at the centre of geopolitical partnerships,” the report, titled “The Great Game in the Pacific Islands,” predicts.

For many low-lying islands in the region, rising sea levels and increasingly severe weather events pose a real and immediate threat to their territorial integrity, economic stability, and the safety and security of their citizens.

Cyclones have increased markedly in number and severity since the 1970s, data from the EM-DAT International Disaster Database shows.

Severe tropical cyclone frequency in the Pacific Islands. EM-DAT Database via Lowy Institute

The Lowy Institute notes that responding to climate emergencies in the region has become a new front in the battle to win allegiance from Pacific states, with “larger powers … jostling to be first and preferred responders to climate and humanitarian emergencies, sometimes complicating local response efforts and delaying delivery of assistance to affected communities.”

Sending assistance, usually in the form of military vessels and personnel, “involves securing rights to use ports, airstrips, and maritime routes,” which can then help open the way to a more permanent presence.

However, the recipients of that help would prefer “greater local capacity-building and alignment with national emergency response systems, rather than duplicating efforts with incompatible systems and command structures.”

The report concludes that “climate change is the single biggest security concern in the region.”

‘Price Setters’ in Influence Auction

While the land masses involved are small—albeit some are strategically positioned for defence purposes—Pacific nations’ proximity to vital maritime routes is of key interest to the larger nations vying for a favour.

Located between Asia, North America, and Australia, whichever global power establishes alliances in the region can exercise control over transport routes, telecommunications assets, critical infrastructure, and the region’s globally valuable assets, from fisheries to seabed minerals.

Several existing or potential deep-water ports in Pacific countries are valuable for both commercial and defence purposes, allowing ship servicing and resupply. The Pacific is also crisscrossed by undersea cables that are vital for global communications networks.

As the Institute notes, these small nations have an asset equal in value to that of the most powerful nations on Earth—a vote at the United Nations.

With Beijing seeking to exert its influence across the region—an effort the report characterises as “indefatigable”—and pushback against that from the United States and its allies, Pacific Island nations have realised they can leverage that competition.

To do so, they have become “price setters” rather than simply taking whatever is offered by their traditional allies.

Previously, Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong said Canberra and its partners are locked in a “state of permanent contest” with Beijing over influence in the region.

The report notes that “hardly a week goes by without a new initiative by Australia and others—involving more aid, more loans, or more defence cooperation—to counterbalance China’s deepening reach into key sectors such as policing and telecommunications.”

“Pacific Island countries are asserting their needs more boldly in international engagements, asking for better deals on trade, labour mobility, digital connectivity, and climate resilience,” the Lowy Institute said.

Constantly Shifting Power Balance

Australia has opened six new Pacific diplomatic posts since 2017, part of 18 new regional embassies. Meanwhile, four have closed.

After Beijing pushed it out of Nauru, Kiribati, and the Solomon Islands with promises of substantial investment in local infrastructure, Taiwan has been left with just three Pacific countries offering diplomatic recognition: Palau, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands.

Emabassy openings and closing in the Pacific since 2017. Lowy Institute Global Diplomacy Index

The Chinese Communist Party’s deal with the Solomon Islands in 2022 caused particular alarm, allowing Chinese “police, armed police, military personnel and other law enforcement and armed forces” deployments and, with the Solomon Islands’ consent, ship visits, logistical support, and stopovers and transitions there.

At the time, Mihai Sora—a Research Fellow in the Pacific Islands Program at the Lowy Institute and a former Australian diplomat to the Solomon Islands—said the deal “could have security implications for the whole Pacific.”

Western nations responded by seeking to strengthen ties with other Pacific Island nations; there have been 178 bilateral and multilateral engagements between Pacific nations and the rest of the world since 2021.

The key difference, though, is that most of those agreements are publicly available, while the Beijing-Solomons deal is not.

Australia’s Development Assistance Eclipses Beijing’s

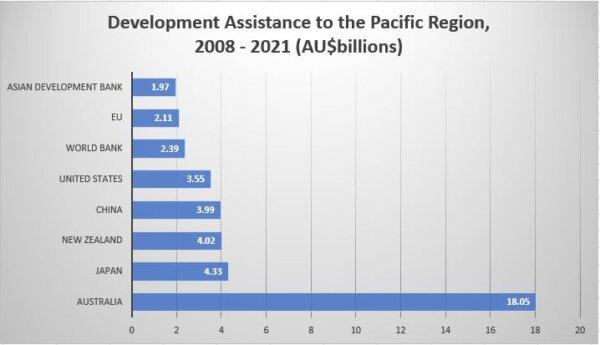

Australia remains by far the largest provider of development assistance to the Pacific, yet the report notes that “while China’s aid appears to be decreasing, its presence and sway are not.”

Development assistance to the Pacific region, 2008 – 2021 (not all donors included) with data from the Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map. Rex Widerstrom/The Epoch Times

Australia has increased aid to a record level of $2 billion (US$1.36 billion) per year, in addition to infrastructure loans and grants of $4 billion through the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility.

Beijing’s cash flows peaked in 2016 but is now more targeted to selected Pacific countries such as Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Kiribati.

“While the amount China invests in the region has dropped, the number of projects, albeit at lower value, has increased,” the Lowy Institute said, adding, “China’s presence remains highly visible and valued by Pacific leaders.”

Pacific countries are trying to keep a delicate balance amongst these competing imperatives, reliant on aid from Australia and New Zealand but also hoping to increase trade and grow their economies by tapping into burgeoning North Asian markets, particularly China.

Papua New Guinea, for instance, is pursuing a free trade agreement with Beijing.

However, Pacific Islands face ongoing structural constraints, including their small economic scale, distance from markets, high labour costs, low skills base, and poor digital connectivity, which leave them dependent on resource extraction and, in some cases, tourism.

The focus at the Pacific Islands Forum this week will be on decreasing dependence on foreign powers while managing the competing demands of Beijing and the United States and its allies—all while trying to ensure that nations remain, literally in some cases, above water.

Source link

Add comment