Commentary

The note mentions the “broader distress brewing in the commercial real estate market, which is hurting from the twin punches of high interest rates, which make it harder to refinance loans, and low occupancy rates for office buildings—an outcome of the pandemic.”

We are used to this kind of language blaming the pandemic for the results of lockdowns. Of course, it was a man-made decision to turn a respiratory virus into an excuse to shut down the world. The lockdowns blew up all economic data, generating seesawing graphs on every indicator never seen in industrial history. They also made before/after comparison extremely difficult.

The consequences will echo long into the future. The high interest rates are a result of trying to slow down the money spigot unleashed in March 2020, in which more than $6 trillion in new cash appeared out of nowhere and was distributed as if by helicopter.

What did the money injection do? It generated inflation. How much? Sadly, we do not know. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) simply cannot keep up, partially because the Consumer Price Index (CPI) does not calculate the following: interest on anything, taxes, housing, health insurance (accurately), homeowners insurance, car insurance, government services like public schools, shrinkflation, quality declines, substitutions due to price, or additional service fees.

Getting the inflation data wrong is only the start of the problem. We are lucky if any government data even adjusts for the wrong numbers. Consider retail sales as just one example. Let’s say you bought a hamburger last year for $10 and you bought one this week for $15. Would you say that your retail spending is up 50 percent? No, you just spent more on the same thing. Well, guess what? All retail sales are calculated this way.

As E.J. writes: “This is factory orders before and after adjusting for inflation: What looks like a 21.1 percent increase from Jan ’21 to Mar ’24 is only a 1.8 percent increase—the rest is just higher prices, not more physical stuff; worse yet, real orders are down 6.9 percent since their highwater mark in June ’22.”

Imagine the same charts but with more realistic adjustments. Are you getting the picture? The mainstream data being dished out daily by the business press is fake. And imagine the same charts above redone with inflation in the double digits as it should be. We’ve got a serious problem.

In addition, neither worker/population ratios nor the labor participation rate are back to pre-lockdown levels.

To calculate whether and to what extent we are in recession, we look not at nominal GDP but real GDP; that is, adjusted for inflation. Two down quarters are considered recessionary. What if we adjust pathetic and seriously mis-estimated output numbers by a realistic understanding of inflation over the last few years?

We don’t have the numbers but a back-of-the-envelope suggests that we never left the recession of March 2020 and that everything has been getting gradually worse.

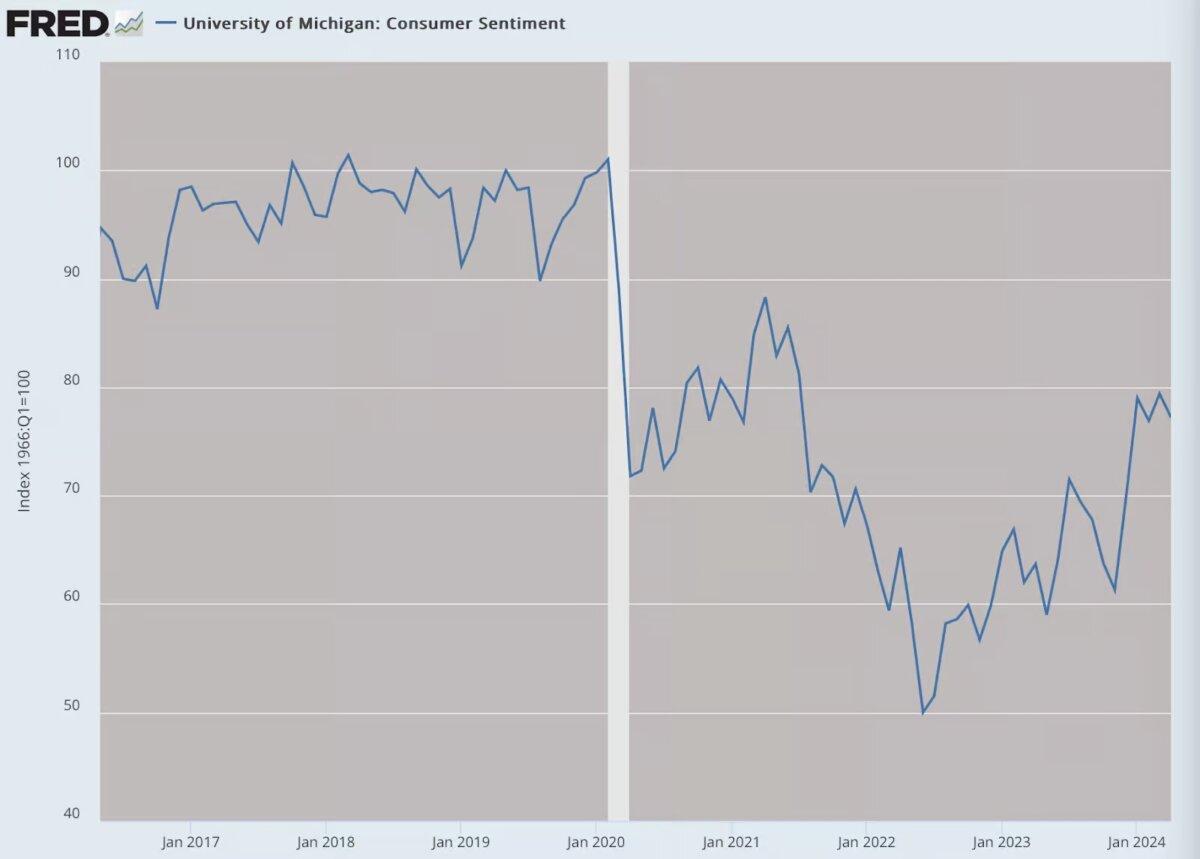

That appears to fit with every single consumer sentiment survey. It seems likely that people themselves are better observers of reality than government data collectors and statisticians.

So far, we’ve dealt briefly with inflation, output, sales, and output, and find that none of the official data is reliable. One mistake bleeds to others, such as adjusting output for inflation or adjusting sales for increased prices. The jobs data is particularly problematic because of the problem of double-counting.

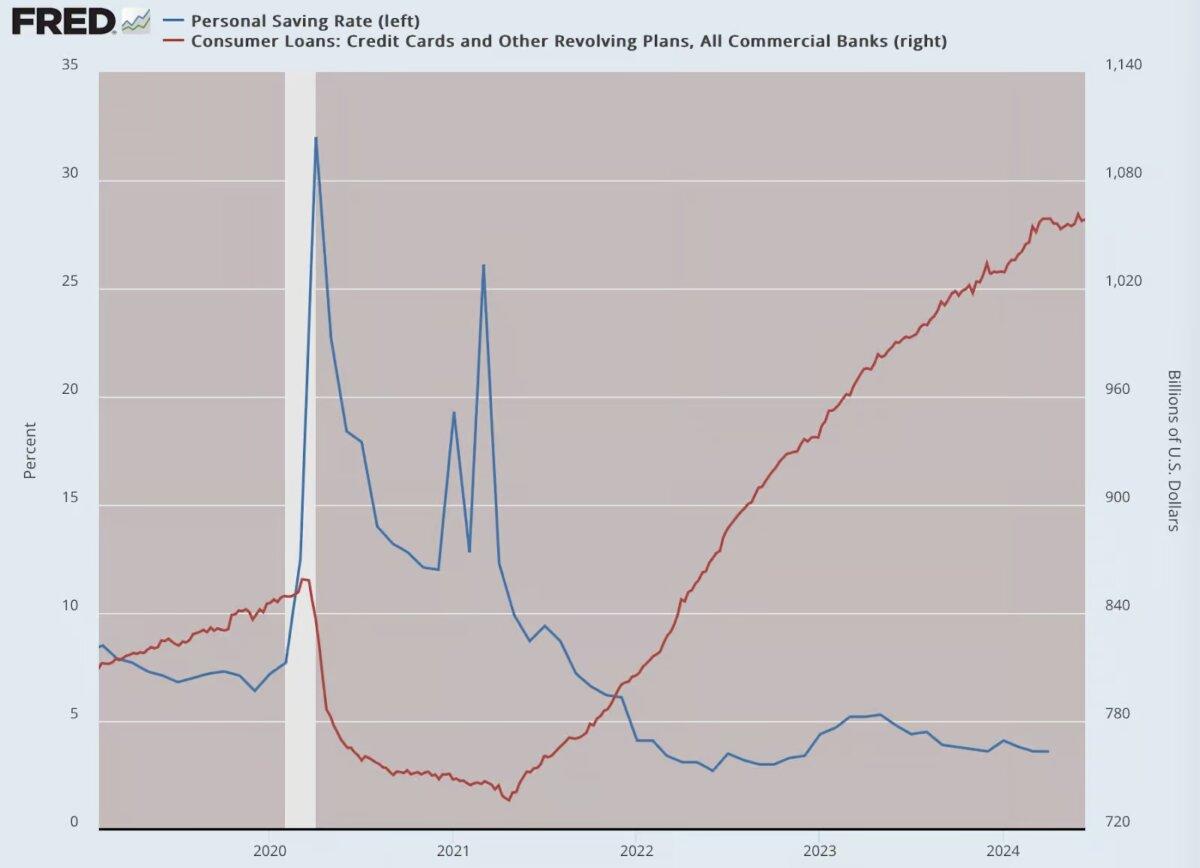

What to know about household finance? The flipping of savings rates and credit card debt tell the story.

When you add it all up, you get a strange sense that nothing we are being told is real. According to official data, the dollar has lost about 23 cents in purchasing power over the last four years. Absolutely no one believes this. Depending on what you actually spend money on, the real answer is closer to 35 cents or 50 cents or even 75 cents … or more. We do not know what we cannot know.

We are left to speculate. And this problem is combined with the reality that this is not just a U.S. problem. The increase in inflation and the decline in output is truly global. We might call this an inflationary recession or high inflationary depression, all over the world.

Consider that most economic models used through the 1970s, and still today, postulate that there is a forever tradeoff between output (with employment as a proxy) and inflation, such that when one is up, the other is down (Phillips curve).

Now we face a situation where the jobs data are profoundly affected by bad surveys and labor dropouts, output data is distorted by history-making levels of government spending and debt, and no one is even trying anymore to provide a realistic accounting of inflation.

What the heck is really going on? We live in data-obsessed times with seemingly magical abilities to know and calculate everything. And yet even now, we seem to be more blind than ever before. The difference is that nowadays, we are supposed to trust and rely on data that no one even believes is real.

Going back to that commercial real estate crisis, for the NYT story, the large banks would not even talk to the reporters doing the story. That should tell you something.

We live with a don’t-ask-don’t-tell economy. No one wants to say hyperinflation. No one wants to say economic depression. Above all else, never admit the truth: the turning point in our lives and the precipitating event to the whole calamity for the world were the lockdowns themselves. All else follows.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.

Source link

Add comment