Our perceptions about what we eat affect how our bodies respond to food.

For instance, when we take in low calories, if we are informed that our food contains many calories, our bodies may respond in a manner similar to eating higher-caloric foods—such is the power of the mind.

Milkshake Research

In 2011, Yale University researcher Alia J. Crum and co-authors published a study in Health Psychology in which 46 participants consumed a 380-calorie milkshake labeled in two different ways, each reflecting calorie content.

One group received the milkshake labeled as “indulgent” with a claim of 620 calories, while the other group received a milkshake labeled as “sensible” with a claim of 140 calories.

Before and after they drank the milkshake, ghrelin—the hunger hormone—was measured in their blood, and their perception of the healthiness of the food was also assessed.

The indulgent label group reported a much lower perception of the healthiness of the food compared to the sensible group.

The indulgent label group exhibited a dramatically steeper decline in ghrelin levels after drinking the shake, whereas the sensible group showed a relatively flat ghrelin response.

Two groups drank milkshakes with the same ingredients but with different calorie information on the labels. The group whose labels read 620 calories had a steeper decline in ghrelin (representing feeling full). The group whose label read 140 calories had a relatively flat ghrelin (representing feeling less full). Illustration by The Epoch Times

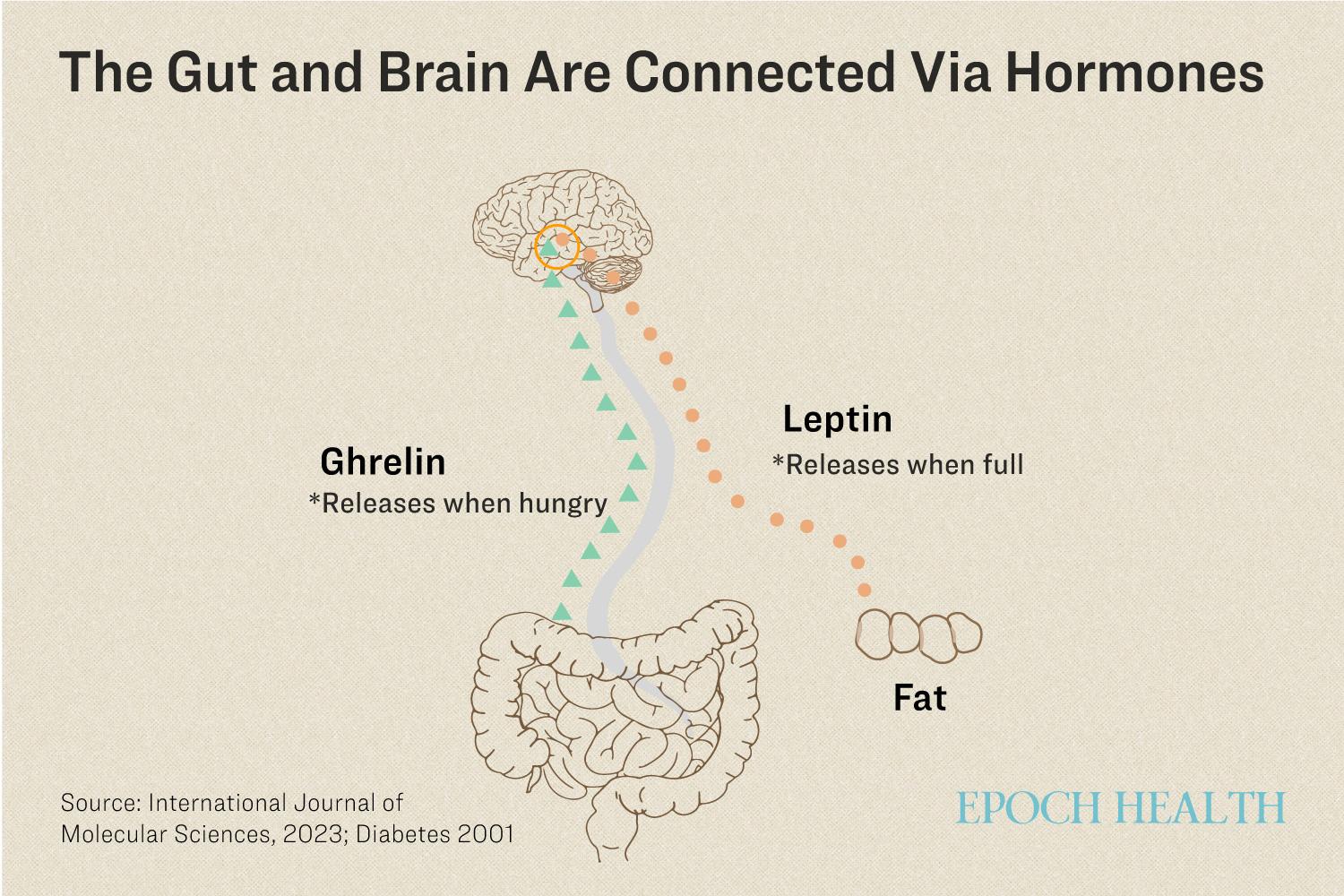

Ghrelin is a hormone that signals hunger, whereas the hormone leptin signals fullness. The former is released into the bloodstream by the gut when a person is hungry, whereas the latter is released from fat cells when a person is full.

Ghrelin is a hormone that is released into the bloodstream by the gut signaling hunger. Leptin is a hormone released from fat cells that signals fullness. Illustration by The Epoch Times

Poor Communication

In people with obesity, ghrelin does not reduce after a meal, and the brain does not receive the fullness signal.

Experimenting With Hormones

Since the discovery of ghrelin, scientists have tried to develop therapeutics targeting ghrelin-related pathways to treat obesity, however, due to the potential adverse effects in brain-rewarding centers, to date, there has been little success.

Researchers have also experimented with another hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in weight loss. GLP-1 is released after eating, thus regulating appetite and body weight.

Mindfulness Helps Holistically

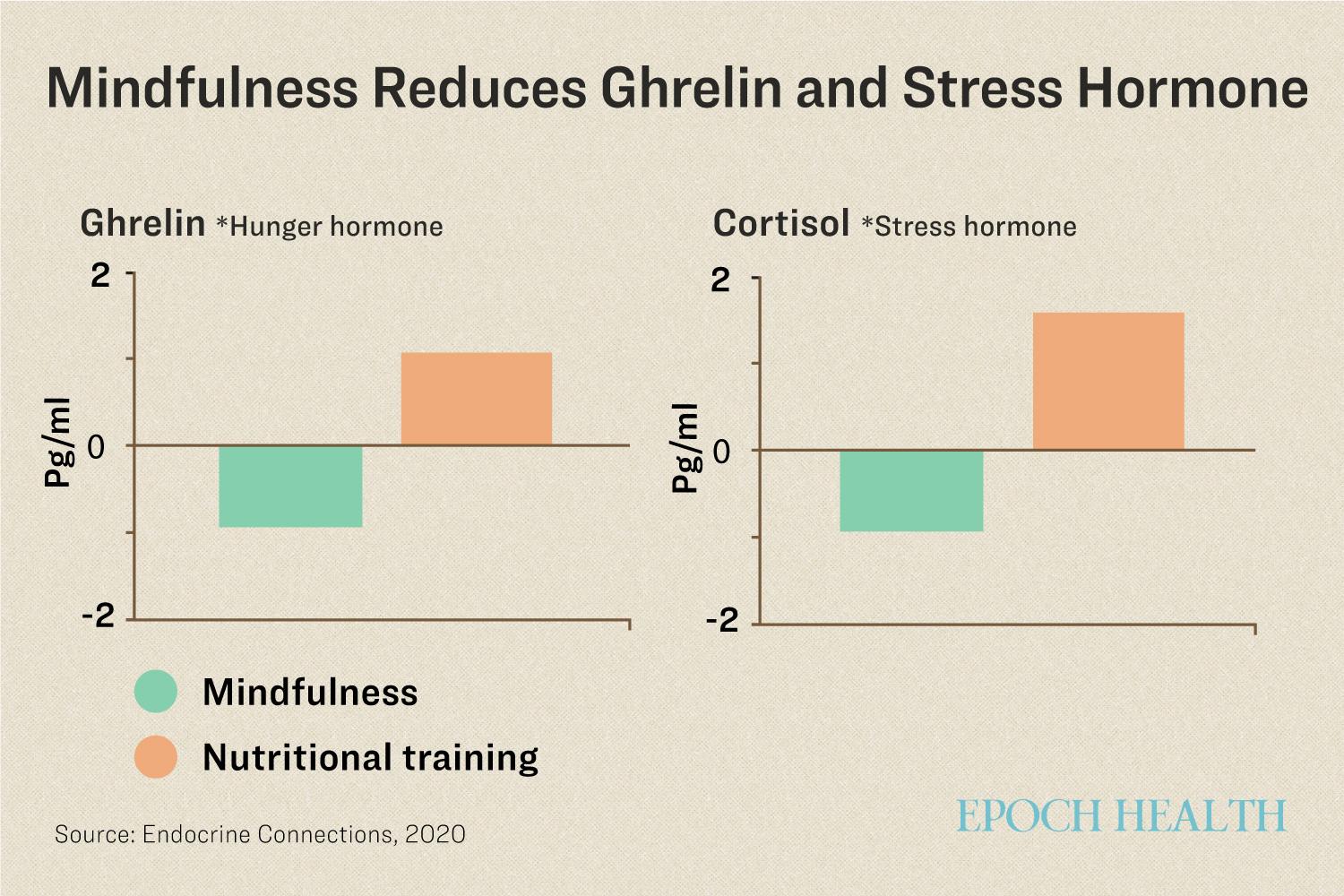

In a 2020 study, Mexican researchers assessed the effects of an 8-week mindfulness-based intervention on body weight, appetite regulators, and stress in 45 school children with coexisting obesity and anxiety.

One group received an 8-week conventional nutritional intervention (diet) and the other an 8-week mindfulness-based intervention. The mindfulness intervention focused on improving body awareness, increased awareness of eating, and understanding emotions.

Before the study began, the kids had similar body fat, ghrelin levels, leptin levels, and other measures of health parameters.

After eight weeks, the kids in the mindfulness group experienced declines in anxiety and body fat. Their ghrelin and stress hormones were also reduced. In addition, at 16 weeks, they had experienced a lasting decrease in body mass index (BMI).

After eight weeks of mindfulness training, the kids in the mindfulness group experienced significant declines in ghrelin and stress hormones, compared to those kids who received normal nutritional training. Illustration by The Epoch Times

In contrast, the kids in the conventional nutritional intervention group—who didn’t receive mindfulness training—experienced increases in ghrelin levels and a more moderate decline in BMI.

The results indicate that training your mind can help recover the normal mechanism in the gut-brain axis possibly via the two key hormones—ghrelin and leptin—and ultimately help with weight loss.

What We Eat Influences What We Like

As our minds can affect how the molecules in our bodies react, what our bodies do can restructure our minds.

Repetition of certain stimuli can change our preferences for different things we sense, like tastes and smells. This has been shown in many studies, especially with foods and flavors.

Research has shown that people develop food preferences based on exposure. This exposure effect can be leveraged to improve relationships with food.

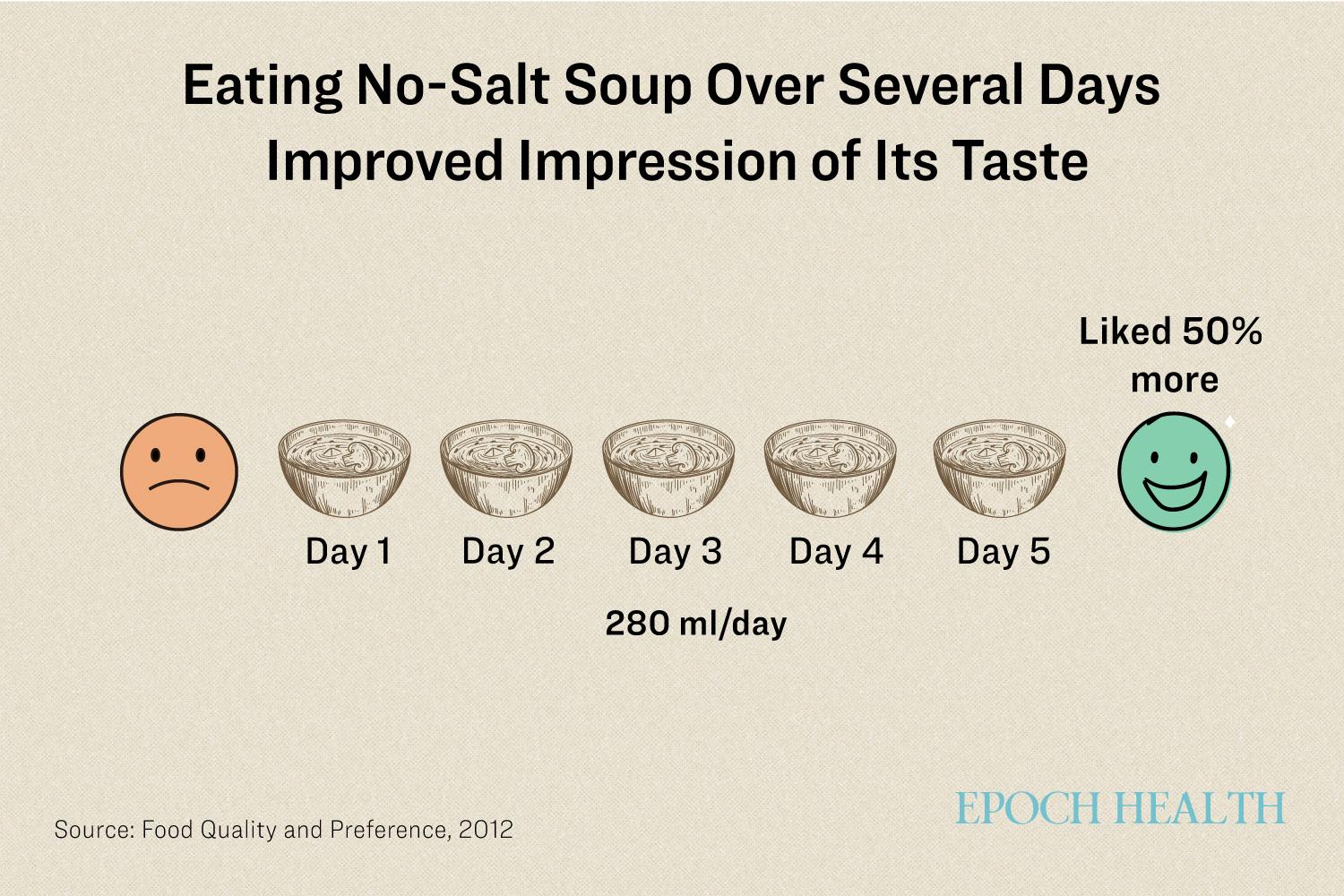

Following an initial assessment of liking, familiarity, and saltiness of six soups varying in salt content (0–337 milligrams (mg) sodium chloride/milliliter (ml)), 37 participants, previously assessed for their preferred salt level in soup, were allocated to three groups into a main study.

The first group tasted small samples (20 ml) of soup with no added salt; the second group received a large bowl (280 ml) of the same no-salt soup; the third group tasted small samples (20 ml) of soup that contained an added salt of 280 milligrams/100 grams.

The soups were served once per day for eight days for all subjects. The assessments were done again on non-salt soup.

After eating 20 ml per day of the no-salt soup for three days, participants liked the soup 27 percent more than before. After eating 280 ml per day of no-salt soup for five days, participants preferred it 50 percent more.

There are similar changes in the rating of familiarity with the no-salt soup.

These results indicate that simply tasting the no-salt soup multiple times was enough to make it as enjoyable and familiar as salty alternatives.

A 2012 study showed that people who disliked soups without added salt liked them after eating them multiple times. Illustration by The Epoch Times

If you’ve become accustomed to ultra-processed food, you can train yourself to enjoy real, whole foods alternatives. The more you eat such foods—the more you’ll like them.

Food for Thought

The complexities of our human body involve much more than individual preferences—it’s about harmonizing the intricate relationships between the millions of cells in our bodies, gut, brain, our food choices, and even our mindset or views on food.

Ultimately, effective solutions do not have to be complex. Simple, accessible methods are often right at our fingertips—we just need to be open-minded and ready to reconnect with the lost conductor of our health.

Source link

Add comment